Quayola Takes Us Through Transient: Impermanent Paintings in DC

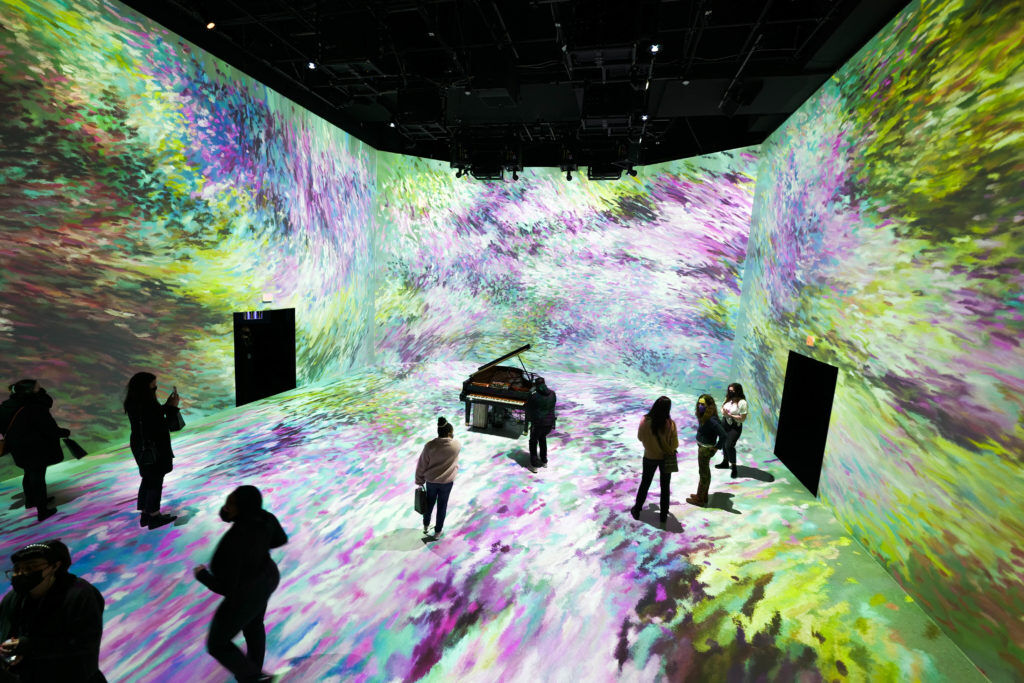

Now on view through March 6 at our Washington, DC space is an immersive exhibition entitled Transient: Impermanent Paintings by the Milan-based multimedia artist Quayola. The presentation provides an inside look at how music and sound interact when computed with algorithms designed to move beyond human capabilities. Here, a rare series of audiovisual paintings—created with new technology that supports generative algorithms—are projected in communication with unique musical scores, immersing the viewer in unforgettable washes of color and sound. Visitors are encouraged to explore music through a contemporary lens, rethink the relationship between the heritage and future of sound and image, and experience the techniques of human-machine learning for audiovisual creativity anew.

“What is unique about this exhibition is the exploration of synergy between sound and image,” said Sandro Kereselidze, ARTECHOUSE Founder and Chief Creative Officer. “Quayola presents this as performance art, but at ARTECHOUSE, we have transformed it into an exhibition where the performance continues to exist and engage with the visitor even after the artist has left. We believe this is an important step towards a new way to experience a live music performance.”

The exhibition shows a performance created by Quayola, once performed in real-time, with brushstrokes coordinated to appear with each note. At its center is a piano infused with specific software to present visual representations as audio is played. The unique 21-century piano—a Yamaha Disklavier DC7X ENSPIRE PRO—acts as a conductor to show what is possible beyond human potential and capabilities, representing notes in conjunction with brushstrokes at an otherwise imaginable pace.

Through a three-part presentation, guests can get a firsthand look at how the exhibition was made, produced, and presented with: a behind-the-scenes installation dedicated to the technical and creative processes behind the work; a multi-screen audiovisual installation with automated motorized controllers; and a video projection alongside prints of visuals from previous iterations of the main installation. With these three components, Transient: Impermanent Paintings leaves an impression far beyond the museum’s setting.

In celebration of his exhibition, ARTECHOUSE spoke with Quayola to learn how this one-of-a-kind exhibition was developed, how he considers technology in his practice, and what the future of audiovisual work may be.

You worked collaboratively with the ARTECHOUSE team to present this exhibition. Can you take our readers behind the scenes, and share what the starting point was?

Transient is the result of many, many years of experimenting and looking at certain kinds of strategies for audiovisual creation. Transient is really the hypothesis of the research that has lasted for a long time. The process wasn’t really related to the immersive environment; wasn’t really relating to these complexities. It started much earlier with very simple problems that we were trying to solve. How can you create two things at the same time, visual and audio, without hierarchy? How do you create audiovisual compositions? There’s no software really made for these things; no infrastructure that would really allow for this kind of creation. So, to really make this, there’s been a lot of research into creating this work.

ARTECHOUSE came in when this project was maturing in terms of research, but really at a moment where the question arises: “How do we materialize this?” How can this really become a physical experience? Their really unique work, plus projection and sound systems, allow us to really create something truly immersive. We keep hearing about VR, which of course is an interesting prospect, but at the same time, especially coming after this unusual pandemic, something physical, something so profoundly immersive, cannot be compared to what you can see on a VR headset. The resolution cannot be compared to the massive resolution you’re exploring here, and so on. ARTECHOUSE really enabled us to create, and put out something in a way that we really envisioned in the first moment we started this project.

How did the title of your exhibition, Transient: Impermanent Paintings, come to fruition?

Transient is a technical term used in electronic music to define certain picks of the audio spectrum. The transient is this pick where things happen, in a way. It’s a kind of data that can be extrapolated from the audio signal to drive something else. If you look at the work, it is based on these impulses—these transients. It felt like an interesting metaphor for the whole project.

For “Impermanent Paintings,” I like to describe this whole thing as paintings. This metaphor is very inspired by [Wassily] Kandinsky, and the way he used terminology as a way of the art process itself. He started calling his paintings “compositions,” which was a musical term, not used for a visual realm. So, the idea of mixing these two elements together to really blend them was part of the concept.

The idea of “impermanence” is also crucial to the work. For us, it’s not really about making a piece of music or a specific painting. It’s about exploring the infinite potential of certain algorithms that we develop. We will develop systems that are not used to make just one image or one progression, one sequence of piano notes. These are made to explore potentials around a certain logic that are infinite. The idea of changing these over time is very exciting.

What has been a challenge with Transient that you turned into a strength with the exhibition? How did you collaborate with the experimental musician, Seta, to do so?

Traditionally, what I’ve been doing has been mostly rooted in visual art. However, music has been an incredible driving force of all that the studio has been doing, and an inspiration for the past 20 years. At some point, to figure out a way to embrace this language but using the same methodology, the same conceptual framework to actually create music that would meet the same overall language, has been a great challenge. And a great aspiration of mine for many years.

At some point, I started this collaboration with Seta and we started researching different ways that music could be produced. How could you make a score? This of course is an area where there’s been a lot of research in the past. The idea of graphic scores, and painting music, dates back to [Wassily] Kandinsky. But with today’s technology, how can you embrace this idea of generating scores in unconventional ways? The fact that both myself and Seta are not traditionally trained musicians, the way we related to music and harmony is very different. We’re not trying to replicate something or make something better, we’re simply trying to find completely new paradigms of creating that and expressing creativity in that realm in a very different way.

Technology, on this side, is becoming a collaborator that allows us to do that in very different ways. You cannot separate the images from the sound. With the way these things are made together, it’s really interconnected. When you compose music, and you’re able to be influenced by what you see, it changes the way you make the music. The same way these algorithms react to the instructions we provide them, they change the way we think about it. It’s not just technology aiding our ideas; technology really shapes our ideas in real-time as we make the work.

How does Transient: Impermanent Paintings explore creation beyond human capabilities?

This is the result of a very long process—a very long software development—where we created a system, the software, that allowed us to create and compose music and images in real-time. So, both images and music have a relationship with heritage. On one side, we have these modified classic pianos, that are mounting some monitors—special pianos made by Yamaha—that integrate this technology that is possible to talk to them via computational means. On the other hand, visually, there are these pictorial simulations so that the images you will see in the show are related to our pictorial tradition. They simulate images we are familiar with, but end up with behaviors that are completely unfamiliar.

That’s also the crucial point of this whole project—touching on heritage, but playing with it in a way that’s beyond human capabilities. So, what will happen with the piano without the limitation of ten fingers? What happens if you play the piano without the limitations of human movements and limbs? How fast can you play a piano? How precisely can you do that? And so on. At the same time, that happens in the visual realm. What happens if you could paint 200 brush strokes per second? What will this look like? All of these dynamics are not really in place to mimic what you could do without technology, without the systems, but the whole point of this work is to explore what could be done—and how we can express ourselves beyond our human capabilities. How something so traditional that is so familiar to us can be expanded augmented beyond our physical capabilities. This goes, of course, to our physical body, but at the same time, to our mind. How technology can expand the ideas behind creation itself.

What is the relationship between technology and your creative practice? Does time or location impact that?

On one side, there is technology as a driving force of what I do, and somehow looking at the future of what creativity, and aesthetics, could be. But at the same time, I do this by looking at the past. Looking at our historical radiation and our heritage, and probably this is me growing up in Rome, and being born in Rome has an impact on that. So, it’s probably a very personal journey to somehow combine this heritage of where I am from to what this new means of expression can do.

All of my work really deals with this relationship between past, present, and future. Between heritage and the history of the visual languages that we celebrate from the past. And new modes of expression, new modes of doing things. So, the work that I’m presenting here is really a combination of all of these different apparatuses. Transient, explores new ways of creating relationships between sound and image—something that of course exists for a very long time, however, technology has never been really available to create a seamless interaction between these elements.

You mentioned being inspired by the idea of technology, not just the technology itself, anchored in the past, present, and future. How do you envision machine- and human-thinking in the future?

Technology is seen as a tool to really make ideas possible, but I’m very intrigued by the idea that the human mind can be really augmented by technology. So, ideas that you would not be able to even conceive are there because of this exchange with technology. The relationship between human and machine is really at the core of this project. The algorithms that we developed for the creation of these works are in part autonomous. They have their own autonomy, let’s say, but at the same time they only work in conjunction with the human aspect. We—myself and my collaborators—control this system, these algorithms in real-time, to actually produce something, but our actions are driven by the response of these algorithms. So, it’s really this relationship between these two very different ways of thinking that’s creating what you’re seeing in this exhibition. It’s a very hybrid composition, and world, between human thinking and machine thinking. Human aesthetics and machine aesthetics. For me, that’s the interesting future that I imagine—not so much in this autonomous world. Rather, in this exchange.

What do you feel is special about ARTECHOUSE and the ecosystem it is creating to support this medium?

ARTECHOUSE is really an incredible example of the ambitious thinking that these types of processes, this type of art, has a place. And should be celebrated as a physical experience. With all of these new adventures in NFTs and ways of ultimately making money about exchanging digital files, I think it’s also full of excitement, but it’s bringing us to this level where physical experience somehow doesn’t really matter. And I think what we’re doing here really tried to challenge that. There is so much more of what you can look at on your phone, or your computer screen. Digital art can become a very, very physical experience if supported with the right apparatus, the right technology, the right infrastructure.

ARTECHOUSE is really a very rare example of infrastructure to allow artists to deal with expressing digital technology, digital artistry, into the physical realm. What we’re seeing here is a very physical experience. To me, that’s what it’s all about.

If you’re in the Washington, DC area, we hope you will come see Transient: Impermanent Paintings.

Recent Posts

Walking Through World of AI·magination

Step into a world that could not have been created

ANNOUNCING THE WINTER ARTECH·TALK SERIES WITH NASA: CONVERSATIONS BEYOND THE LIGHT

This winter, join us for a continuation of our sold-out

ANNOUNCING THE FALL ARTECH·TALK SERIES WITH NASA: CONVERSATIONS BEYOND THE LIGHT

This fall, join us for illuminating ARTECH·TALK programming at ARTECHOUSE